Are we not all broken in one way or another? Is it not true that from the moment we breach our mother's wombs we are broken? Is not the harsh reality of leaving our water paradise to be thrust into the cold world not a breaking of sorts?

Mark W. Bundy, the author of "'Know Me Unbroken': Peeling Back the Silenced Rind of the Queer Mouth", wishes to know Gloria Anzaldua unbroken "just as Maria Lugones wants all muted women 'to be seen unbroken'" (qtd. in Bundy 139). Bundy's article is lyrical/poetical at times with his use of imagery and rhythm. But I keep asking myself what is my reaction to the piece? What have I taken away from my reading?

Language.

The beauty of language. The ability of language to build bridges through its human use. These are things that I absorbed in my reading. When discussing Anzaldua's use of language, Bundy writes: "These ongoing harvestings of yours, Gloria. Peeling it all back--culture, self, body, voice, sex, identity, meaning, realities, love, illness, recover" (140). All things can be discovered and known through language. Understanding can occur through language and its use.

If we are silent in our anguish, our fear, our anger, our love, our passion, how will anyone understand? We need to make room for everyone's language, not just mine, not just yours: and yet, mine and yours. In the words of the Na'vi (Avatar) "I see you." That is what we should all be striving for by listening to the language of others.

According to Lorin Schwarz, arts-informed research "holds within it an imperative not only to question its own completeness and objectivity, but also to 'speak back' to forms of authority that have traditionally silenced and left out voices that either don't fit, refuse to offer a definitive answer or that demand emotional knowing in order to understand what they feel compelled to say" (29). Schwarz, in her article "'Not My Scene': Queer Auto-Ethnography as Alternative Research Method." argues that research can benefit from this type of methodology.

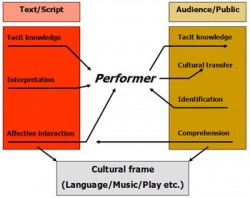

How does one reflect on something as profound and somewhat mind-boggling as the concept that some topics are enhanced by this type of methodology? When I contemplate this method, I envision this diagram that I found online: With this type of research, things that would otherwise be left unnoticed are brought to light: the "human" elements that are not, scratch that, NEVER black and white. Schwarz argues that this type of research "provides a critical foundation to question the structures we take for granted in often unexamined dualisms of 'black and white' thinking" (29). Humanity, when viewed as black and white, becomes this rigid, unbending thing that breaks when the slightest pressure is put on it. This type of research allows the researcher and the audience to see things in shades of gray.

Schwarz demonstrates her arts-informed research with a play. A one man act that explores what one man feels when he sees other happy gay men together. This is the type of auto-ethnography that perhaps no other type of research can get at at this depth. Some of the passages get at the depth of human existence in a way that regular, black and white, research never could.

"Adjectives are a way of constraining and controlling. 'The more adjectives you have the tighter the box.' The adjective before writer [ex: feminist writer, lesbian writer] marks, for us, the 'inferior' writer, that is, the writer who doesn't write like them [the dominant culture]" (Anzaldua 264). Adjectives are labels, and in Gloria Anzaldua's article "To(o) Queer the Writer--Loca, escritora y chicana," she discusses, among other things, some of the implications of using labels.

As I have advocated before, I do not like labels, and I avoid using them for myself at all cost. But often, we are faced with situations where we are forced to use them to define ourselves. I could say that I am an Appalachian woman (said correctly), or what some would consider a hillbilly. And I would wear that identity proudly, but as Anzaldua notes, that would place me in a box, and a quite tight fitting box as well.

So if I didn't like that label, I could say that I am a feminist, or a lesbian, or a rhetorician (I'm NOT a speller), or a middle-class white woman, or, or, or. As you can see, the list could go on and on forever. To chose any ONE of those labels and say this is me, would be to deny those other parts that are just as important and just as vital to who I am as any other label. I would, in essence, be dividing and splitting my identity: who I really am.

Anzaldua drives this point home when she argues so eloquently that "identity is not a bunch of little cubbyholes stuffed respectively with intellect, race, sex, class, vocation, gender. Identity flows between over, aspects of a person. Identity is a river--a process. Contained within the river is its identity, and it needs to flow, to change, to stay a river--if it stopped it would be a contained body of water such as a lake or a pond" (267). I wonder what my first-year composition students would think of this quote. The 18 years-old students who felt that by the time you enter college your identity should be pretty much set!

Anzaldua discusses more than just labels and identity with in this article, which is apparently an excerpt from a larger piece, but it is her comments about identity that resonate the most with me. Is there such a thing as a lesbian writer, or a queer one for that matter? I don't know, but I do not wish to cling to just one small part of my identity and be labeled that way.

I would not normally blog about an appendix in a text, but when it comes to Mary L Gray's text Out in the Country, I think it important to consider what Gray has to say.

In this appendix, Gray discusses several aspects of her research methods, including why there were few females in the study. First, Gray discusses how this type of research is next to impossible to conduct due to the difficulty of gaining IRB approval when wanting to talk to youth under 18 without their parents consent. She notes that until these conversations can be brought into the school systems, it will continue to be difficult.

Gray also comments on the fact that her research pool was limited due to starting out with youth already involved in some type of LGBT organization. She states that "this agency-driven approach, however, has significant drawbacks . . . . The most critical shortcoming of relying on agencies: most rural communities do not have formal infrastructures of not-for-profit social services beyond faith-based organizations" (3670-3686). She tapped into the pools of friends of those she did meet in organizations, and this was how she found her research participants.

She believes that the lack of females is, in part, due to the fact that "young rural women were often too busy between work, family, and school commitments to meet with [Gray]" (3717-3733). Rural young women often have the responsibility of caring for siblings while parents are at work or for caring for older adults for the same reasons (3717-3733). Therefore, females had less social time to become involved in this type of project.

Generally speaking, Gray's book brings to light the complexities involved for rural LGBT youth who are trying to negotiate issues of identity and how these youth find ways to be visible while still maintaining a sense of the familial. It is also enlightening to see how the use of media helps these youths find realness in their queerness. Truth be told though, I am happy to be done with the book.

Mary L Gray's Epilogue to her book Out in the Country discusses two things: the vote on Amendment 2 in 2004 to Kentucky's ban on same-sex marriage and what happened to the youth she worked with during her research.

She makes a valid point when she discusses the amendment that passed and banned same-sex marriages in Kentucky, as it has in many states. Often, exit surveys show that voting yes to this amendment has little, if anything, to do with people "hating" or disliking gays or lesbians and more to do with money (surprise, surprise)! Rural citizens in particular often have no access to the most basic of social or medical services, like health care. So when people begin to discuss same-sex marriages that would offer benefits that are normally only available to married people, rural folk, and others, begin to get defensive. As Gray notes, "rural voters who reject recognition of LGBT rights telegraph their own feelings of economic vulnerability, lack of access to social-welfare benefits, and reliance on the material more than symbolic preciousness of marriage to span the gaps in a woefully threadbare social safety net" (3559-3576). When looked at in this light, it begins to make sense as to why these amendments are continually voted into states' constitutions.

The rural youth that Gray spoke with concerning marriage noted that they wanted to have the chance to get married, but they did not seem to care whether or not these marriages would be seen as legal. I would attribute this attitude to their youth, but Gray does not comment on it.

As for what happened to those Gray followed in her research, most have moved on. The Boyd County High Gay-Straight Alliance became defunct once those who began it graduated. The one responsible, in large part, for the Highland Pride Alliance also moved on, and when I attempted a google search, no website was found by that name. Again, I would think that all of these changes are just a product of youth growing and investing their time and energy into different things.

Gray ends her text with many questions for where this research might go from here, such as "what place will young women and trans rural youth find in this field of identity?" (3624-3639). But the story does not end here, and there will be one more post before we call this book quits.

In Mary L Gray's conclusion to Out in the Country, she summarizes the points that she makes throughout the book. But what I find particularly interesting are her arguments about how rural youth do visibility. Gray argues that "rural queer youth rework their disorientation from self, in places that prioritize familiarity through codes of sameness, discourage claims to difference, and have relatively few local 'others' to turn to for queer recognition" (3331-3347). So rather then claim an identity of "otherness", they cling to an identity of familiarity to garner as much local support as they can.

As I've made reference too many times, I grew up in a rural area, and I can't imagine what it would have been like for me to try to claim a lesbian identity during those years. I knew I was different, but I had no way of knowing what that difference was or how to label it. I wouldn't have even thought it was sexual at the time. Unlike many of the youth in Gray's text, I had no way of searching for "what was wrong with me" because of course I knew there had to be something!!! Gray's investigation of how media in general and new media in particular help rural youth work out their identity and find realness in being a rural LGBT youth is critical for helping researchers understand how these youth negotiate this terrain.

For me, it wasn't until I went away to college that things began to make sense to me. However, I was still in a very small town, with no family and only a few close friends, and certainly no internet. Life, for any rural youth in my day who questioned their sexuality or gender, were pretty much doomed for a life of misery until they got it figured out; if they did.

Gray's research is interesting, and there are some things to note in her Epilogue which I will get to in the next post.

I am coming to the end of Mary L Gray's Out in the Country, and as usual, I am looking forward to the concluding chapter tomorrow. That is the problem with doing "whole" books; I reach a point where I'm no longer sure if the meanings I find are the meanings that are intended. This chapter, "To Be Real: Transidentification on the Discovery Channel," deals primarily with the meanings two rural trans youth make out of the Documentary "What Sex Am I?" that aired on the Discovery Channel.

What it seems to boil down to, after all of the theorizing and quoting, is that we cannot, or should not, rely on textual analysis of any one piece to determine its usefulness. As Gray argues, "these narratives of queer realness are compelling not as particular grouping of cinematic, televisual, or digital texts but as situated, discursive practices that mark the local boundaries of LGBT identities" (2811-2827).

She proves her point by describing the realness that the documentary "What Sex Am I?" has on the two youths mentioned: one an MTF and one a FTM. The show had a profound effect on the FTM. He even recorded it so that he could sit down with his mom and watch it. The point being, the FTM has a supportive family, lives within two hours of medical treatment for the transition, and was allowed to leave school and pursue his GED online to avoid the harassment from classmates. When his family makes the two hour trip for medical treatment, they also go see the friends that he has made via his internet connections. Within this context, the documentary opened up an entire new world for this FTM and set him on a path to his true identity.

The other youth, the MTF, has a much different story. When she caught the show on the Discovery Channel, she watched in constant fear that her parents would return any moment and make her turn the channel. She lives in an area where the closest medical treatment would be 4 hours away, she is constantly fearful that her parents will discover what she is searching for on the internet on the computer in the family room (and in fact they did find emails on this topic and took away her internet privileges), and she is still in public school where she worries that others will discover her secret. While the documentary helped make real her feelings, it did little to change her world.

Gray set out to determine "how does it [media] come to matter or to occupy a place of importance in a rural young person's negotiation of queerness" (2845-2860). It becomes apparent that media has to be considered within the context the viewing, not just the media itself.

"What we call 'the closet' springs from the idea that identities are waiting to be discovered and unfold from the inside out. Authenticity hinges on erasing the traces of others from our work to become who we 'really' are. To leave the traces of social interaction visible is to compromise our claims to authenticity and self-determination" (Gray 2780-2796).

Chapter 5, "Online Profiles: Remediating the Coming-Out Story," of Gray's Out in the Country speaks to how media, particularly the internet, plays a role in LGBT identity. The above quote, for me, pretty much sums up the chapter. Identities don't just suddenly unfold from the inside out. Identities are socially constructed. Rural LGBT youth are aware of their sexual desires but finding "realness" for these identities and desires can be difficult.

Therefore, many turn to the internet and to sites like Gay.com to read real coming out stories and to give voice and meaning to their desires and feelings. They often do not know the terminologies used to express what they are feeling until they search the internet for sources to help them understand. So rather than the internet being a place that "turns them" or puts ideas into their heads, it is a place that helps them understand and come to terms with who they are. It is a social place that helps make it all real.

I've often wondered if having a resource like the internet would have helped me come to terms with and embrace my identity much sooner than I did. I fought against my own feelings for years and refused to knowingly place myself in social circumstances that would bring those feelings to the forefront. Perhaps if I would have had the internet, a place where I could have researched and learned in private, things would have been different.

Bottom line is that media is a positive resource for many rural LGBT youth, helping them to learn and understand who they are, making their identities real!

"If rural LGBT-identifying youth are at times hard to see, it is as much because researchers rarely look for them as they have so few places to be seen. They must also be strategic about how they use their communities for queer recognition if they are not to wear out their welcome as locals" (Gray 1867-1883). And this is what chapter 4 of Mary L Gray's Out in the Country deals with: the spaces that rural LGBT folks occupy to become both visible and to work on identity.

Gray makes a good argument for the visibility of LGBT youth in rural communities. But we don't drive down main street, rural town, USA, or the town square and say to our friends, "oh look, there's Billy Bob or Sally Sue at the gay bookstore. I never knew they identified that way!!" And why is that? Well, unlike in the cities, it'd be kinda hard for Billy Bob and Sally Sue to support a gay bookstore in rural town, USA!! And yes, there are probably more than two queer identifying folks in rural town, USA, but it's likely that Billy Bob and Sally Sue are the only two of the dozen or so that do exists that have the couple of extra bucks that they could spend on such luxuries.

So what visibility can rural LGBT possibly have in rural town, USA? Gray describes what she calls boundary publics. Places that are not typically seen as queer spaces can become that when LGBT identifying individuals choose to meet there. Gray argues that "boundary publics therefore should not be seen so much as places but as moments in which we glimpse a complex web of relations that is always playing out the politics and negotiations of identity" (1900-1916). Gray goes on to note that "rural young people make space for themselves through acts of occupation" (1980-1996). Examples she list include doing drag at the local Wal-Mart Superstore, attending a church skate park punk rock concert, and through new media such as websites and blogs.

The point is this: rural LGBT youth, and adults too for that matter, make the space for themselves to be visible. It's not like the locals don't know who is LGBT! Seems that people in my home town knew I was a Lesbian long before I even knew what the word meant. And the fact of the matter is that those who are gay, lesbian, bi, or trans in rural communities are not hiding any big secret. Sure, they don't go around flaunting it because that could do more harm than good, but as one rural youth told Gray "I think everyone knows about me [being gay]. I don't really have to say it" (2090-2106). So if a group of queer identifying people are seen in one place, that place becomes, for the moment, a place for them to be visible as LGBT.

The concept of boundary publics and spaces such as the local coffee shop becoming a place of identity work are new to me. Gray discusses several theorists who deal with the traditional notion of the public sphere and how her boundary publics fit into these theories. Since I am unfamiliar with these theories and theorists, it is hard for me to wrap my mind around all of this on one read, but I believe I have the basics of the concepts: public spaces are plastic enough to stretch and become something they are typically not.

Rather than to split the chapter's up and blog nightly, I have decided to combine the two post together and do them every other night, allowing me to keep the chapters together. No internet in Philly last weekend and illness this week have me slightly behind. That being said, it's time to move on to chapter 3 in Mary L Gray's Out in the Country.

This chapter, entitled "School Fight!", basically chronicles the attempt of students at Boyd County High School to establish a Gay-Straight Alliance (GSA) club at the school. They were turned down numerous times for technical reasons but finally managed to get it approved by involving the ACLU. It wasn't long, approximately two weeks, however, before the school board voted to do away with all clubs at the school. This was seen for what it was: a ploy to do away with the GSA via the backdoor while the other clubs continued to meet.

It wasn't until there was a Unity Rally held that things finally came together. I liken it to the way my family feels about things. . . I can bad-mouth anyone in my family I want too, but let someone else try bad-mouthin 'em and it's likely they will have a fight on their hands. I've learned that this is also the way rural communities work. We can fight amongst ourselves and bad-mouth each other all day long, but don't let no outsider come in and try to spread hate and discontent. This is what happened in this small community as well. During the Unity Rally, while they never exactly embraced the concept of the GSA, it "proved more solidifying than anyone anticipated, thanks in no small part to notorious Kansas-based Westboro Baptist Church minister Fred Phelps" (1668-1685). As one participant stated, "I thought it was important to show these folks from Kansas that a message of hate and intolerance is not something that people in Eastern Kentucky believe" (1685-1703).

Eventually, the ACLU did have to become involved in the situation and they sued the school board, who did not even have the power to decide about clubs in the schools. The case was won and the GSA was once again established in Boyd County High School.

Gray notes that "the situation called attention to the complicated intersection of racial and class tensions that structure rural life" (1721-1737). In areas where people are struggling to find jobs and keep their families fed, clothed, and housed, the thought of any group getting special treatment is threatening. Rural communities are also threatened when groups such as the ACLU become involved. They feel that these urban influences sweep into these rural communities, disrupt everything, then rush back out leaving a mess in their wake. And often, they have a point. But as this example clearly shows, if faced with embracing the queerness that is family or allowing those from Kansas to spread hate among their community, they chose to embrace their own.

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed